'The human heart yearns for contact - above all it yearns for genuine dialogue. Dialogue is at the heart of being human. Without it, we are not fully formed - there is a yawning abyss inside. With it, we have the possibility of our uniqueness, and our most human qualities emerging. Each of us secretly and desperately yearns to be 'met' - to be recognized in our uniqueness, our fullness, and our vulnerability. We yearn to be genuinely valued by others as who we are, even that we are. The being of each of us needs to be revered - by ourselves, but also by others. Without that, we are not fulfilled - we are not fully ourselves.' -- Hycner and Jacobs, 1995

Buddhism, and Chan Buddhism in particular, generally considers discussions of psychology, if not irrelevant, a waste of time. "Just sit." We're told when we ask our teacher about why we fell in love with someone, got angry with our child, felt guilt over not helping a destitute old man on the street. Or we may be told, "work on your hua-tou, don't be distracted by wondering thoughts or emotions." Zen's beauty as a spiritual discipline is in its simplicity and its directness. The practice leads us to uncover a tremendous amount of intuitive understanding of what being alive as a human is all about. But Zen often seems to butt heads with western ideas concerning our psychological constitution, downplaying them, ignoring them, or even discounting them.

However Zen is a practice of inclusivity: we embrace and seek to understand everything that comes to us, integrating it into the matrix of consciousness. A person of Zen welcomes the mysterious unknown as one might a new and delectable morsel of food: we explore it from all directions, with all our senses, until we know its texture, aroma, and taste. To ignore anything is at worst to repress it, at best to pass up an opportunity to learn something new about ourselves.

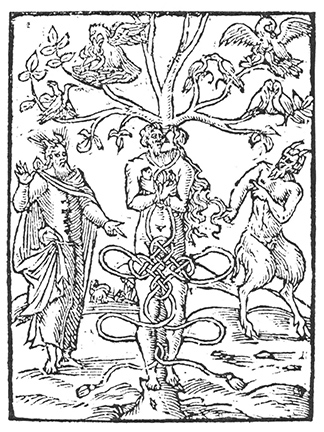

Woodcut from Barthelemy Aneau, Picta poesis, Lyon, 1552, depicting mystical union of male and female, also referred to as Divine Marriage/Divine Union. A rarely discussed topic in Zen circles is the nature of intimacy. Zen doctrine says phooey to human intimacy. Detach from people. Yet we don't need to look far into Zen's history to find a colorful montage of intimate human relationships of all kinds, often of a romantic and/or sexual nature, both bisexual and homosexual. Not uncommon are sexual relationships between sangha-leaders and their disciples, although rarely are they discussed openly. In justification of such relationships, a sangha member may remark: "Whatever Roshi does reflects his profound enlightenment. His actions cannot be questioned by people like us."

Woodcut from Barthelemy Aneau, Picta poesis, Lyon, 1552, depicting mystical union of male and female, also referred to as Divine Marriage/Divine Union. A rarely discussed topic in Zen circles is the nature of intimacy. Zen doctrine says phooey to human intimacy. Detach from people. Yet we don't need to look far into Zen's history to find a colorful montage of intimate human relationships of all kinds, often of a romantic and/or sexual nature, both bisexual and homosexual. Not uncommon are sexual relationships between sangha-leaders and their disciples, although rarely are they discussed openly. In justification of such relationships, a sangha member may remark: "Whatever Roshi does reflects his profound enlightenment. His actions cannot be questioned by people like us."

In China there are sexual relations within monasteries. They are known to go on yet often overlooked and rarely discussed, unless they are adequately blatant: then the monks or nuns may be expelled. While generally taboo, sex is a common thing in all religions. Holmes-Welch tell a story of the monk, “the Venerable Miao-lien” who built the Chi-le Ssu branch temple in Penang. For years there was gossip “of orgies and secret underground tunnels used for vicious purposes”. In 1907 Miao-lien severed off “the whole of his genitalia with a large vegetable chopper.” He died some weeks later.*

A great number of Chinese Buddhist monks spend a few years in monasteries then leave to get married and find a job. It's no different among those in the Occident who connect with a sangha for a period of months or years: the members eventually leave and get into relationships, if they weren't already in them. Those who stay "in service" must come to terms with their sexual nature in an institution that considers sex an anathema.

Humans are social animals and it's for this very reason that we exist in the first place. We have a profound drive to feel connected with another person and to have sex: it's a drive fueled by a mélange of natural chemicals found in our bodies (such as DHEA, various pheromones, oxytocin, phenylethylamine, estrogen, testosterone, serotonin, dopamine, progesterone, prolactin, and vasopressin to mention a few). When the mix is "just right" there's no holding back sexual appetite, or the propensity to "fall in love"; but that's only the physical part of the picture. The other part is, for lack of a better term, a spiritual one: there is an innate desire for our being to be released from its sense of isolation, for it to merge into the greater unity which unconsciously, we know is there. In Buddhism we refer to this greater unity as our Buddha Nature, or our Buddha Self, or our Self Nature or our True Self. Mystics of other religious traditions often refer to it as God.

This force that compels us toward connecting with our True Self is so strong, so overpowering, that we envision it in other people or, in Carl Jung's terminology, we project an archetype onto other people; that is, we imbue the other with superhuman attributes, qualities of perfection, in order to attain the feeling of spiritual union.  The man in love with a woman projects the anima archetype, the woman in love with the man projects the animus archetype, the mother in love with her baby projects the "divine child" archetype, etc. Such projections give a person a tremendous sense of elation and joy … which lasts for as long as the projection is maintained. But such projection also requires some amount of reciprocal projection back from the other person. The moment the projection is terminated by either party all manner of emotional fallout ensues. The pain from the dissolution of two-people-as-one is generally in proportion to the force of projection prior to the dissolution.

The man in love with a woman projects the anima archetype, the woman in love with the man projects the animus archetype, the mother in love with her baby projects the "divine child" archetype, etc. Such projections give a person a tremendous sense of elation and joy … which lasts for as long as the projection is maintained. But such projection also requires some amount of reciprocal projection back from the other person. The moment the projection is terminated by either party all manner of emotional fallout ensues. The pain from the dissolution of two-people-as-one is generally in proportion to the force of projection prior to the dissolution.

Hycner and Jacobs, in the leading quotation, describe this natural yearning to be 'met'. In clear contrast to Zen lore, they say that in order to be fully ourselves we must be revered by ourselves, as well as by others. Isn't this exactly what happens when we join a Zen sangha? We revere the leader, portraying him or her as above and beyond the understanding of an unenlightened being (projection of the "wise old man" or sage archetype), and we in turn receive his projection on us (or our imagined projection, usually the child archetype). When hormones and body-chemistry get involved, these projections can readily switch forms to the anima and animus. And don't we sometimes feel a bit special, even inflated, when we become an accepted member of a sangha?

Guan Yin, the Chinese Buddhist Celestial Savior, is depicted here pouring the “dew of compassion” from her vase into the child.Often overlooked in Zen training in the West is the profound importance of the Celestial Savior. All religions offer such an <imagined> "divine being" as a replacement for human-to-human projections of ideal forms. In Buddhism we have Meytrea, also known as Guan Yin (Kannon). The meditator, instead of projecting the anima or animus on a person, will use mental imagination, faith and devotion, to project upon the divine-being, thus circumventing the need for a human target.

Guan Yin, the Chinese Buddhist Celestial Savior, is depicted here pouring the “dew of compassion” from her vase into the child.Often overlooked in Zen training in the West is the profound importance of the Celestial Savior. All religions offer such an <imagined> "divine being" as a replacement for human-to-human projections of ideal forms. In Buddhism we have Meytrea, also known as Guan Yin (Kannon). The meditator, instead of projecting the anima or animus on a person, will use mental imagination, faith and devotion, to project upon the divine-being, thus circumventing the need for a human target.

These are considered advanced meditations insofar as the practitioner must have already passed through many earlier stages (including Samadhi). Hsu Yun puts this at "stage 7" in his ox herding poems: "Into this painted hall comes a spinning red wheel. The New Bride finally arrives, and from my own house!" Jalaluddin Rumi offers a similar observation: "The minute I heard my first love story, I started looking for you, not knowing how blind that was. Lovers don't finally meet somewhere. They're in each other all along." As one can imagine, a mind made powerful through years of meditation can invoke tremendous sexual energy from these meditations - the term orgasmic ecstasy is not used indiscriminately to describe their arousing effects!

If these meditations are thwarted for any reason when the practitioner is ready for them, having freed himself or herself from the restraints of repressed feelings, including those related to intimacy and sex, the practitioner can easily revert back to projections upon people again.

However we wish to inspect the nature of intimacy, its attainment is the greatest of all desires. It has inspired poets, artists, song writers, sculptors, dancers, scientists, mathematicians and mystics in all cultures throughout history. And it's all for the yearning to be met, for the ecstasy of completeness.

* The Practice of Chinese Buddhism 1900-1950, Holmes Welsch, Copyright 1967 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.