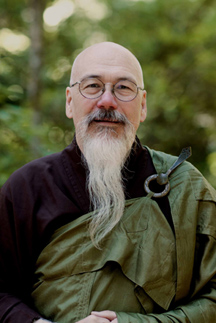

Introduction by Chuan Zhi

As Zen grows in popularity in the United States and other occidental countries, there are growing demands for its representatives to provide for the needs of those Zen enthusiasts incarcerated in prisons. Only a couple of decades ago it was virtually unheard of for Zen clergy to minister to inmates in prisons, yet today it is a very much growing and needed service. While the Order of Hsu Yun has a history of providing ministerial services to inmates around the country over the last decade, our most active prison ministries are spearheaded by Rev. Fa Xing Shakya in Western Washington State. In the following article, Fa Xing describes how he came to become one of the most active Zen Buddhist ministers for many of the prisons in Western Washington. He also discusses the nature of these ministries, and some of his experiences as he developed a unique approach to working with this most underserved population. - Chuan Zhi

A Brief Account of my Prison Volunteer Work

The Antecedents

A couple years ago, some friends and I were invited to visit another sangha during their annual celebration of the Buddha’s enlightenment. We had a wonderful time there – getting to know their sangha members, enjoying a wonderful feast, and watching the entertainment. The entertainment was top-notch, including a short play about the Buddha’s final moments and an elaborate series of traditional island dance routines put on by a Samoan dance troupe. We were having so much fun that we lost track of time, and even forgot where we were. We were brought back abruptly when one friend commented on how the food reminded him of the fare at a local restaurant. He made an off-hand remark to one of their sangha that they should stop and eat there sometime. The sangha member replied that he’d love to do that in a couple of years . . . as soon as he was released from prison.

This was my first exposure to life on the inside.

The Beginnings of a Prison Ministry

I live in a small, rural, relatively conservative town about two hours west of Seattle, Washington. The predominant religion in the region is the various forms of Christianity, with a small population of practicing Jews as well. In this town, other religious traditions (such as Islam, Buddhism, Wicca) are each generally represented by no more than a dozen or so people, most of whom don’t congregate or practice as a group.

About four years ago, by chance, I discovered that another Zen practitioner had moved to the area. He had temporarily taken a job as the facility chaplain at Stafford Creek Corrections Center (SCCC), the state prison just outside of town. His tenure at that job had already ended when I met up with him, but he had decided to remain in the area because he liked living in the small town. As I got to know him, I learned that he was, and still is, very committed to making the dharma available to people in prison. One day, he informed me that he had been invited to the SCCC prisoners’ annual Buddha Day celebration. Having previously committed himself at another prison event elsewhere, he asked me and a few others to go in his stead. We accepted his invitation and were eager and anxious to see what lay ahead, as none of us had ever been in a prison setting before.

We learned more about the event as the day approached. The Washington State Department of Corrections recognizes about a score of ‘official’ religions to which the inmates can claim membership. Each religion is granted one annual holiday celebration, during which they can buy and prepare their own special food, invite family and friends and special guests, put on entertainment, and conduct a religious service or ceremony. The Christian groups usually celebrate Christmas or Easter in this fashion, while the Muslims practice Ramadan, and so forth. The Buddhist groups usually combine a celebration of the Buddha’s birth, enlightenment, and death into one event, calling it Buddha Day or Buddha Fest.

On the day of the event, we were joined by some Theravadin monks from a Thai temple in Olympia, which is about an hour away. Along with them, we were the special guests at that year’s celebration. The event was wonderful, as I described above (I should mention also that the Samoan dance troupe was an inmate group – and just as impressive as anything I’ve seen on the outside). It was a complete revelation to most of us, and certainly to me, to meet and spend time with these men in prison. Many of us had been conditioned for years to believe that all people in prison are ultra-dangerous, psychotic, drug-addicted, serial murderer/rapists/arsonists with no socially redeeming characteristics. We were then quite surprised to meet so many well-mannered, sincere people. There were even times during the event when it was quite easy to forget where we were, as in the story I related above.

In the course of the event, I had a chance to speak with the facility chaplain, who oversees all religious activities, services, and events at SCCC. He mentioned that the Buddhist group had been lacking a sponsor for the last couple of years, and asked if any of us would be interested in filling that role. The sponsor, as we learned, functions much as a chaperone, allowing the men to meet in groups. Regulations prohibit the men from congregating without a specified purpose, and without a sponsor to ensure that that purpose is served. A religious sponsor (as opposed to a sponsor for a secular group, like Alcoholics Anonymous) has the additional responsibility of leading religious services for the group. In the absence of an outside volunteer, the chaplain himself had been sponsoring the Buddhist services, since all of the recognized religions have a right to congregate. As chaplain to 2,000 men, he was understandably anxious to have that part of his workload lifted from his shoulders.

Having had my eyes opened to aspects of prison inmates that I had never before imagined, I was intrigued by his request and volunteered on the spot. Elated, the chaplain rushed me through the volunteer orientation process (their once-every-three-month training turned out to be that night!), and I was cleared as a volunteer in just a few short weeks, a process that normally takes months.

Before I officially began, I asked the chaplain if I could attend one of the regular Buddhist services, to see what the men were already doing. He agreed to show me, and had me accompany him on a Thursday afternoon for the monthly service. It quickly became clear that the situation needed improvement. The chaplain, Christian by faith, did not lead or help the men with their service, but left them to their own devices. He simply sat in the back until they were done. The meeting was held in a large classroom, with about forty chairs all facing the front. A handful of men had set up a nice, simple altar from the group’s religious property box, and the same handful of men performed the service. They had a pamphlet that was written to provide Buddhist basics to inmates (the refuges, precepts, four noble truths, heart sutra, etc.) and they read it cover-to-cover, though it was clearly not designed to be used that way. While they did this, the twenty-five or so other men split into small groups to chat, without any regard or attention paid to the service. The chaplain informed me that this was the typical process. In fact, he had cut the meeting time from two hours to one, because the service took about fifteen minutes and he did not have time to stand around to watch the men chat.

Such was the backdrop against which my prison volunteer service began.

The Early Days

Though I was new to the prison environment, I had my friend’s counsel to help guide me early on. He advised me that men on the inside cannot usually handle meditation sessions longer that 10 minutes or so. Familiar with Stafford Creek CC in particular, he also explained that there were two distinct ‘factions’ to the Buddhist inmates there. He called one the ‘Anglos’, the European-descent cultural Americans who were only interested in meditation and didn’t like all of the Asian religious practices. The other consisted of the cultural Asians, who were more interested in being led in a religious service – to them, meditation was something that monks did.

In addition to this, I recognized from the beginning that prison culture is a microcosm of culture outside the walls. In the outside culture, Buddhism is still a minority religion in the USA, so the same is true on the inside. So while there were (and are) dozens of Christian volunteers, hailing from various sects (Catholic, Evangelical, Seventh-Day Adventist, Mormon, etc), I was the only Buddhist volunteer. This meant that I would be addressing men with a greatly varied background in Buddhism. Since my own training and experience are specifically in the Zen tradition, I could not reasonably expect to teach the men Tibetan Buddhist practices, or lead Theravadin services. What I could do, though, was look to the basics – The Refuges, the Precepts, and the Four Noble truths.

So, I put together a service that we have followed, with minor variations, to this day. According to the official schedule, we meet for two hours, from 7:00pm to 9:00pm. The reality is slightly different – movement, which is the name for the time announced each hour when the inmates can go from one location to another, starts around 7:00pm, but usually doesn’t end until about 15 minutes later. The same happens around 8:00pm. The final movement is technically at 8:45pm, since the men have to be in their cells at 9:00pm. So really, we have about 30 to 40 useable minutes each hour.

To begin, we arrange our space by moving all of the furniture to the edges of the room, then lining up two rows of chairs facing each other. Between the rows, at one end of the room we set up an altar, and I sit on my cushion at the other end. We begin standing, all facing the altar, and we recite a few verses dedicating the space. I then go up to the altar and light three sticks of incense, pausing with each stick for us to recite the refuges together. We then recite the five Precepts before taking our seats. I lead a ten-minute meditation period, giving some instruction any night that we have new people. Following that, we do an incense offering, allowing any one of the group to go up to the altar and offer incense and bow, with the rest of the group standing and facing the altar, bowing as the person up front does. Then I speak and take questions for five to ten minutes until the 8 o’clock movement is called. At this point, most of the men leave, leaving just a handful for the second hour. The second hour begins with 5 minutes of Japanese-style walking meditation, or kinhin. We then sit in meditation for about 20 minutes before putting the room back in order and ending the session for the night.

This format seems to have worked quite well over time. Those men looking to be led in a religious service (including most of the cultural Asian men) seem to be satisfied with the recitations and incense ceremony and offering during the first hour, while those looking for more meditation (mainly the ‘Anglos’) really enjoy the second hour.

Lessons Learned

From the beginning, as I’ve said, I have arranged the room so that everybody is sitting in two long rows, facing each other. I happen to like this setup anyway, and it is the norm in the various zendos that I have practiced in. For the prison setting, I find that the fact that everybody can see each other to be very helpful. It makes communication easier, keeps everything open, and ensures that everybody is participating and paying attention. So while I still have about the same number of people that were attending before I came, now they are all involved, instead of just a handful of them.

As with all new enterprises, the early days had a fair share of adjustments. For instance, after some disruptions early on, the men came to me at one point and requested some social time, explaining that because of restrictions, the time spent in the Buddhist service was the only time that many of them could see each other. Because of this, some of them were fidgeting, whispering, and signaling during the meditation period. After talking it over with them, I agreed to allow about ten minutes of idle chatter before beginning each evening, which the men were very grateful for. Once we began that arrangement, disruptions disappeared almost immediately.

Despite my friend’s early advice, I’ve found that many of the men are able to handle longer meditation sessions quite well. I believe this is true in part because of the social time I allow them at the beginning, which gives them a chance to get their active energy ‘out of their system’ before settling in to sit still. I think it also has helped to have a shorter meditation during the first hour, so those that are interested primarily in the service can handle it, while only those interested in longer meditation stay for the second hour. Those that do stay for the longer meditation are very grateful – since prison is such a noisy environment, the quiet time spent with me is a rare respite for them.

I have also learned that the men usually want me to talk and answer questions for much longer; they would be satisfied to simply listen to me the whole time! This, I have discovered, is one of the main benefits they get from my presence. After all, they can sit meditation on their own, and they can read books about Buddhist teachings, practices, and philosophy. But to have a live person to interact with, to answer their questions about practice and how to apply it to their lives, is a rarity for which they are very grateful.

Branching Out

After volunteering at SCCC for a while, I started working with Fa Lohng Shakya, who lives an hour to the east of me. He was volunteering at another prison, Washington Corrections Center (WCC), and I arranged to join him. The two of us now jointly lead that inmate sangha, going in a couple of hours a day, two times each month. Most times we go in together, but we also serve as back-up for each other on days when one of us cannot go in.

At WCC we also set up two rows of seats facing each other, but WCC’s sangha has a set of 10 zabuton and zafu (donated by Fa Lohng and a Tibetan Buddhist volunteer) that we use to sit on. We sit for 20 minutes, do kinhin walking meditation for 10 minutes, sit another 20, then have a dharma talk and discussion. WCC is unique, in that it is the ‘processing center’ for the Washington state prison system. That means that every inmate in Washington goes to WCC immediately after sentencing, where they spend a few days to a few months getting ‘processed’ – sorted, tested, psychologically evaluated – before being distributed to the other prisons in the system. There is only a small permanent population at WCC, and those are the inmates who work at that facility (the janitors, cooks, etc). This means that, except for 2 or 3 individuals, the Sangha is different every time that we go out to WCC. While this keeps us from establishing a long-term practice relationship with most of the men, it also provides us a continual practice in “Beginner’s Mind”, since every visit is a fresh start.

There are two more prisons not too far from where I live, both to the north of me. One of them, Olympic Corrections Center (OCC), lies about 2 hours away. The other, Clallam Bay Corrections Center (CBCC), is about an hour beyond that. About a year ago, an inmate in my Stafford Creek sangha told me of his time at OCC, and the volunteer who was leading Buddhist services there. That volunteer was coming from Seattle, which was a four hour trip, one way. I decided to contact that volunteer to see if she was interested in working together, much the same way that Fa Lohng and I do. This would give her a much-needed back-up, especially considering that my commute to OCC was half as long as hers. She was very receptive to the idea, and we started the process to get me cleared as a volunteer there. As we were working out the details, though, she had some changes in her life that required her to withdraw as a volunteer, so she asked me to step up and be the sole Buddhist volunteer at OCC.

I readily accepted, and continue to go out that way once every two months. Because of the length of the commute and the long stretch between visits, I spend 6 hours out there when I go (always on a Saturday), to justify the drive and to allow the men more time to practice. These visits are structured very similarly to my Stafford Creek visits, but the longer time period allows for more repetition – more meditation, more kinhin, more dharma talks and question and answer periods.

OCC is a ‘camp’ prison. This means that it is for men with 2 years or fewer left on their sentences. It is a small, minimum security facility (it was a surprise the first time I saw inmates walking outside the perimeter fence!) in the middle of the old-growth rain forest adjacent to Olympic National Park. Most of the men there work in partnership with the Washington state Department of Natural Resources (DNR) out in the woods – planting trees, harvesting trees, clearing roads, repairing storm damage, and so on. The surroundings are beautiful, and it’s an interesting irony to note that these men are being forced to live in a location that many of us would be willing to pay a lot of money to live in!

Coincidentally, when I first started looking at volunteering at OCC, the Buddhist volunteer at Clallam Bay (CBCC) was looking for a guest speaker for their annual Buddha Day event. Fa Lohng and I took up the invitation, and went together for their event last year. The volunteer and the men were thrilled to have us and excitedly asked if we could come regularly. Due to the time and distance involved, as well as other obligations, Fa Lohng couldn’t come more than once a year or so, but I agreed to come up every three months, which I’ve continued to do.

CBCC is a fairly large prison, like Stafford Creek. The man who volunteers there is an older gentleman with a long history of solitary practice. He is a joy to talk to and graciously allows me to stay at his house every time I go up to CBCC. He greatly enjoys having me as a guest teacher, turning over the whole program to me, and has even told me that he’s borrowed some elements of my program to incorporate into their regular practice there.

The Practice Continues . . .

So now I volunteer regularly at four prisons (and Fa Lohng even serves a fifth one farther to the east), and the more I go inside, the more I learn. Though all part of the same Department of Corrections system, each prison has a completely different feel to it. Different physical layouts, security levels, staff, chaplains, and inmates all contribute to each facility’s individual ‘personality’. Each is a far cry from the stereotyped world of dank, dusty, rusty-barred cages full of inhuman monsters that need to be kept away from the (so-called) civilized world. In fact, far from being the monsters that most people think they are, I’ve found the men inside are not so different from my friends, my relatives, and myself. Some may be repeat offenders, while others may have simply made one bad choice too many. But they are all human, and all of them have the same basic drives, longings, and needs as any of us. And the same sufferings. That much, at least, I can help them with.