The universe, governed by power and the law power obeys, conforms to a dualistic principal of yin and yang, eros and logos, shakti and Shiva. We cannot separate them. Only through spiritual labor can we succeed at reconciling and integrating the noumenal with the phenomenal, the mathematical formula with that which obeys it, and only then can we hope to create the long awaited convergence of science with religion.

The universe, governed by power and the law power obeys, conforms to a dualistic principal of yin and yang, eros and logos, shakti and Shiva. We cannot separate them. Only through spiritual labor can we succeed at reconciling and integrating the noumenal with the phenomenal, the mathematical formula with that which obeys it, and only then can we hope to create the long awaited convergence of science with religion.

And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.

To anyone who is both religious and trained in science, this Biblical line has both a poetic and reasonable interpretation: we imagine the thunderous proclamation that initiated a dazzling creation, that momentous sound of the Big Bang, the reverberations from which we still can hear as background radiation.

In physics we learn laws -- the words that constitute divine fiat -- and we study the effects of those laws upon the stuff of the material universe. But we realize that reason and imagination do not necessarily constitute spiritual love and faith, the emotion of religious belief. Something more is needed. Logos may be fulfilled by reason; but eros is not served by imagination only. The missing "something" that is required is spiritual experience, experience that transcends reason and defies all samsaric imagination.

In the absence of spiritual experience there is a terrible imbalance between logos and eros that creates discord and disputation, for too much of one is as bad as too much of the other. Ever since science was forced to separate itself from established religion's dogmatic assertions, there has developed a breach that is more like a wound.

Since the early days of Copernicus, Science has insisted that it has the power to answer all mankind's questions about the universe. If we fail to understand a phenomenon we need only to investigate it further: give it more time, we say, and eventually we'll discover the true nature of the mystery. We follow the dictum that everything obeys physical laws that cannot be violated. How can we argue with gravity and electromagnetic waves when we use the technologies that come from understanding them? Religion could never have given us cellular phones, space travel, and Nintendo 64.

Science seemed to be so futuristic, so dynamic, always moving forward into new and exciting areas. Religion, on the other hand, was static. Nothing ever changed. In a conservatism that seemed to go from static to stagnant we preferred new religious icons: calculators and computers, digital cameras and video players.

Our Gurus reassured us. Stephen Hawking insisted that there was no need for a cosmic creator because, according to theory, the universe has no boundary conditions and so there never was a beginning and will never be an end. Who needs a creator when there is nothing to create? Carl Sagan spoke often against the religious feeling in man. He described human beings as nothing more than "starstuff."

But we always had that nagging doubt that there was somebody who knew science and also knew that missing "thing". We were not quite comfortable or satisfied with our icons and our gadgets, with those additional billions of galaxies Hubble showed us, with the fascinating and fantastic theories about n-dimensional space-time continuums, intermediate vector bosons, intergalactic dark matter, or anything else in all the flux.

It was easy to ignore the mystical journey that Isaac Newton embarked upon during the latter part of his life (natural laws became uninteresting to him when he discovered the mystical laws that govern rapturous states of meditation).What did he know about curved space and Energy and its Mass equivalence? But we couldn't dismiss the greatest mind of our century so easily: and there we found Albert Einstein holding his own on that peculiar religious turf.

To Einstein, it was the religious "feeling" in man that provided the ultimate motivator for all great achievements. He recognized that without the noumenal, knowledge of the phenomenal was nothing: "The knowledge of truth, as such, is wonderful; but it is so little capable of acting as a guide that it cannot prove even the justification and the value of the aspiration toward that very knowledge of truth. Here we face, therefore, the limits of the purely rational conception of our existence." He continued, "Objective knowledge provides us with powerful instruments for the achievements of certain ends; but the ultimate goal itself and the longing to reach it must come from another source."

When we began to doubt that we could think ourselves to the truth, modern physics began to take a turn in its thinking.

In the December 2002 edition of Wired, Gregg Easterbrook addresses the subject of science and religion in his article, The New Convergence. Easterbrook suggests that scientists, in their quest for understanding the fundamental nature of everything from the origin of the universe to life itself, are beginning to discover god: that we are entering a new era where science and religion are converging.

Easterbrook's article reminds us that, despite our preoccupation with the one side of science, unity requires the other -- the eros -- to balance the logos. The outward view of the universe that, collectively, we create by a consensus of mind requires the inward view that, individually, creates us by a secret message of the heart.

Outwardly, we learn about our physical environment, our location in the universe. Inwardly, we are able to place meaning -- a feeling and a value -- upon our place in the universe. Logos and Eros. Rationality alone leads only to power. Empathy alone stultifies progress. Without the two together we live like animals, killing without conscience, taking what we need without caring what the loss might be to the one from whom we have taken it.

Carl Jung noted that "feeling" was the inferior function, the one opposed to "thinking." For a man to achieve wholeness, it was necessary for him to blend these two opposites together. In the religious life we see the perfect illustration of this principle in the popular tai chi symbol of two commas, one black and the other white, wrapped around each other to form a circle: a symbol of completeness, wholeness. Each propels the other in a harmonious system. [Stare at the tai chi symbol with a calm, focused mind and soon the two commas will begin spinning.].

Carl Jung noted that "feeling" was the inferior function, the one opposed to "thinking." For a man to achieve wholeness, it was necessary for him to blend these two opposites together. In the religious life we see the perfect illustration of this principle in the popular tai chi symbol of two commas, one black and the other white, wrapped around each other to form a circle: a symbol of completeness, wholeness. Each propels the other in a harmonious system. [Stare at the tai chi symbol with a calm, focused mind and soon the two commas will begin spinning.].

Religious literature and iconography are replete with references to this essential balance of logos and eros. When modern science chooses to look away and ignore these icons of wholeness, we find that a one-sided poverty develops. When the mind perceives reality only from its thinking mode, personal values of feeling and value are neglected.

Once we recognize that we exist independently of our thoughts, we can understand that reality exists independently of us and of our thoughts. Reality does not depend upon our psychology, mood, or on what we believe or don't believe - just as our sense of self, of personal value, does not depend upon an ability to contemplate complex physical principles.

What can we expect when we embark on the journey inward? We discover depths of emotion within us -- not sentimental or shallow emotion, but deep feelings of awe, wonder, joy and rapture. This does not detract from our knowledge of quantum chromodynamics or astrophysics, it enriches it!

What can we expect when we embark on the journey inward? We discover depths of emotion within us -- not sentimental or shallow emotion, but deep feelings of awe, wonder, joy and rapture. This does not detract from our knowledge of quantum chromodynamics or astrophysics, it enriches it!

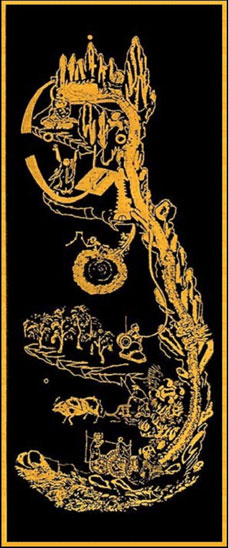

We also become privileged to an assortment of intriguing experiences -- experiences that seem more real than those in the physical world. As the Daoist tablet from Bei Yun monastery illustrates, the way requires hard work: the maiden spins her thread, the plowman furrows his field, the paddlers at the water wheel raise the sacred fluid up the spine. Discipline, dedication, humility, and faith in the path are all required. The journey consumes us on every level -- emotional, physical, and spiritual -- and no aspect of our lives is overlooked. The joy of discovery draws us onward.

The universe, governed by power and the law power obeys, conforms to a dualistic principal of yin and yang, eros and logos, shakti and Shiva. We cannot separate them. Only through spiritual labor can we succeed at reconciling and integrating the noumenal with the phenomenal, the mathematical formula with that which obeys it, and only then can we hope to create the long awaited convergence of science with religion.

When we achieve this we can occasionally put down the chalk or turn away from our computers, look out the window, and reflect with the Psalmist, "Lord, When I consider thy heavens, the work of thy fingers, the moon and the stars which thou hast ordained, what is man that thou art mindful of him?"